In this third edition of Spotlight on a Scientist, we feature Sibley Duckert, a master’s student at the University of Calgary, whose work explores the hidden world of the marine microbiome in Arctic waters. Working in Nunatsiavut and aboard the CCGS Amundsen, Sibley studies how marine bacteria and archaea respond to diesel contamination and contribute to ecosystem recovery following spills. Her research sits at the intersection of microbiology, contaminant science, and Arctic stewardship, and is grounded in close collaboration with local partners and the Nunatsiavut Government. Through her work, Sibley embodies the care, collaboration, and commitment needed to protect fragile Arctic ecosystems.

What is your research focus, and what projects are you working on aboard the Amundsen?

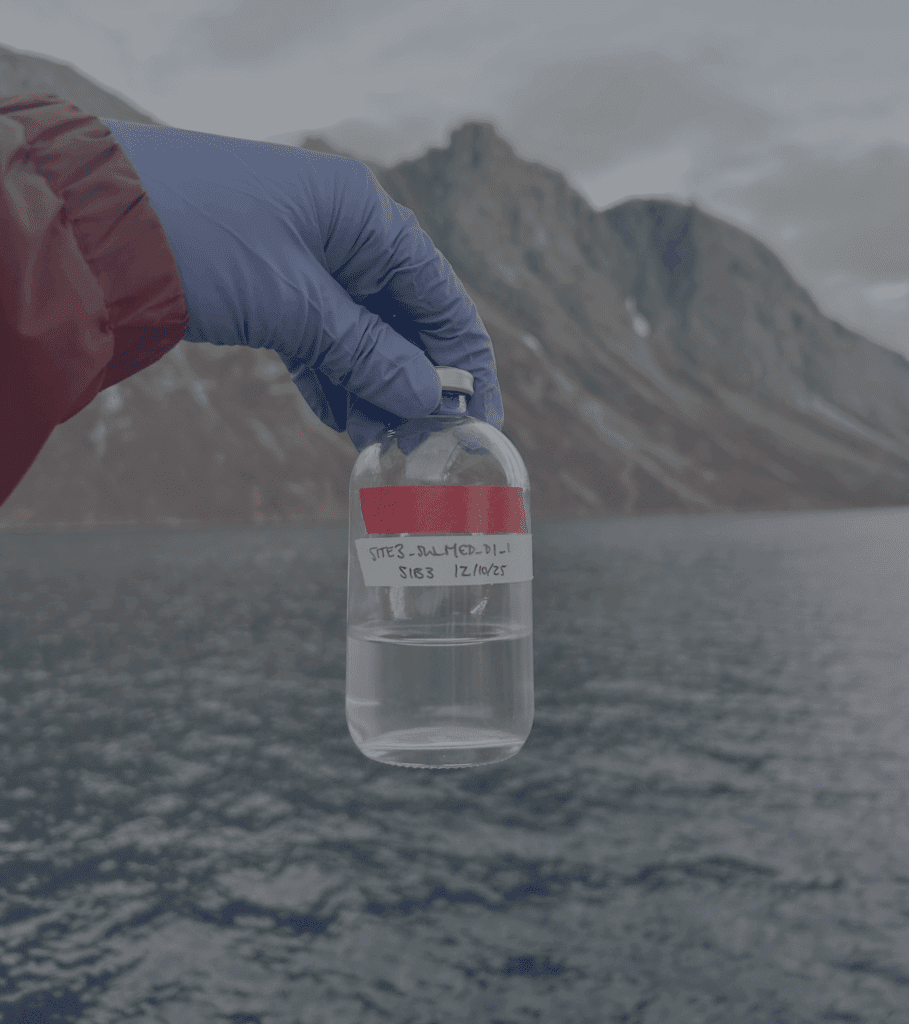

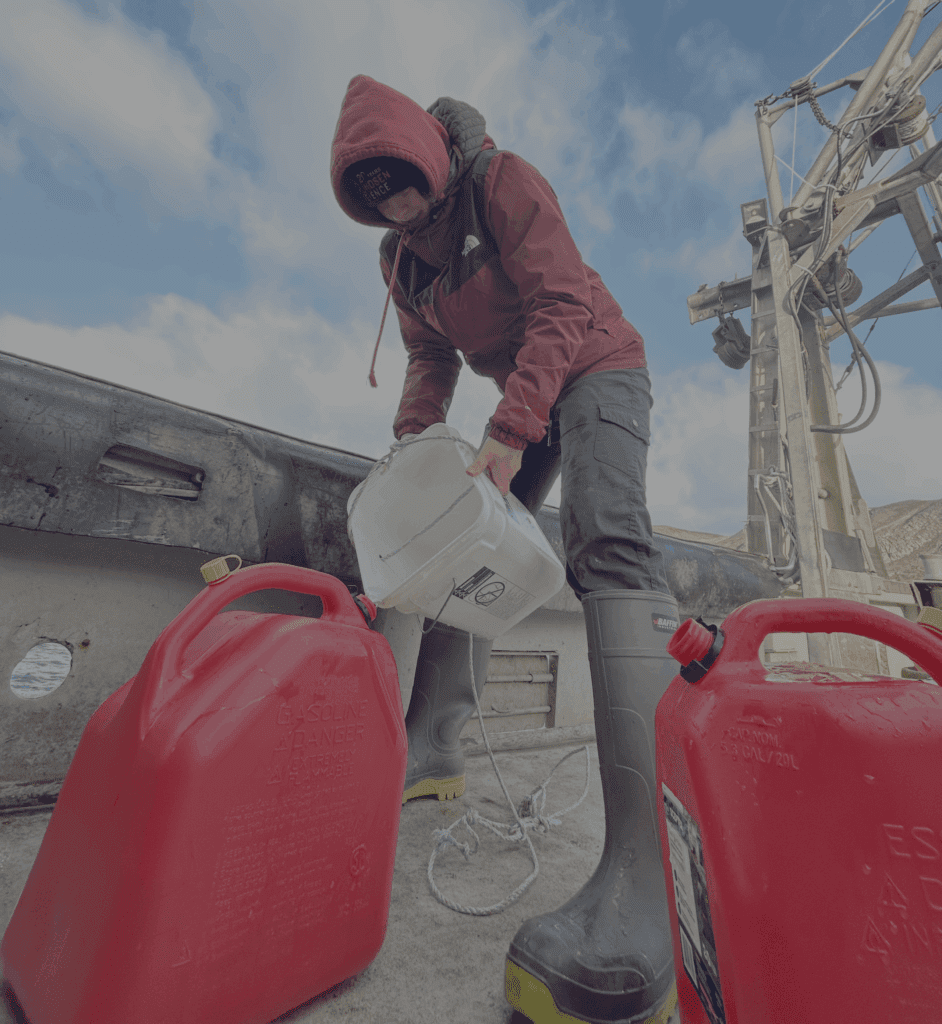

I work in Nunatsiavut, studying the marine microbiome – the bacteria and archaea that are invisible to the naked eye but play a critical role in nutrient and carbon cycling. My research focuses specifically on contaminant cleanup, looking at whether marine microbes can naturally degrade diesel following spills.

In 2020, there was a diesel spill in Postville, linked to fuel offloading for community energy needs. Diesel contaminants were found in Arctic char and seabird eggs, directly impacting traditional food sources and local livelihoods. This made it especially important to understand how the ecosystem responds.