To give you a closer look at the people behind Arctic research, we are launching a new series: Spotlight on a Scientist. Each article highlights a researcher aboard the NGCC Amundsen, allowing them to share their passion, fieldwork, and their challenges.

During the fourth Leg of the 2025 Amundsen Expedition, we asked Adam Garbo, PhD student in glaciology at the University of Ottawa, questions about his research project. Adam studies the life cycle of icebergs in the Canadian North. Discover his background, his projects aboard the Amundsen, and what fascinates him about the Arctic, through his own words.

Can you describe your research subject and the projects that lead you on the Amundsen?

My research is focussed on better understanding the life cycle of icebergs in the Canadian Arctic. This begins with studying glaciers by measuring how thick they are, mapping the landscapes hidden beneath the ice, and identifying the areas where icebergs are most likely to break off. From there, I track the icebergs as they drift into the ocean. Together, these pieces help us better understand how much ice is stored in the Canadian Arctic and what role it plays in sea-level rise and climate change.

On the Amundsen, I am measuring glacier thickness in the Queen Elizabeth Islands using an airborne ice-penetrating radar system. The radar is towed beneath a helicopter and sends signals into the ice; the time it takes for the signals to return reveals how thick the ice is. Many glaciers in the Canadian Arctic remain poorly measured, and these surveys will help fill those gaps, improving our understanding of glacier behaviour and future ice loss. I am also deploying Cryologger tracking beacons, custom instruments I designed and built, directly on icebergs to monitor how they drift. By following icebergs in real time, the beacons provide new insights into how they move through Arctic waters.

What motivated you to pursue this field of study?

The Arctic is changing faster than almost anywhere else on Earth, and glaciers are at the heart of those changes. Icebergs capture that change in a very visible way. They break away from glaciers, travel long distances, and slowly melt into the ocean. Yet there is still much to learn about how they form and how they move.

Their behaviour is not only fascinating to study, but also important for understanding global sea-level rise and the risks to Arctic shipping and coastal communities. I was motivated by the chance to combine fieldwork, technology development, and modelling to better understand these processes and their importance for Canada’s North.

How has your experience onboard been so far? Is there a memorable moment you’d like to share?

Life aboard the Amundsen has been a rewarding and unique experience. It is a rare opportunity to collaborate with researchers from many different disciplines while directly contributing to Arctic science. It has also taken me to parts of Canada’s North that few people ever see, bringing a real sense of exploration to my research.

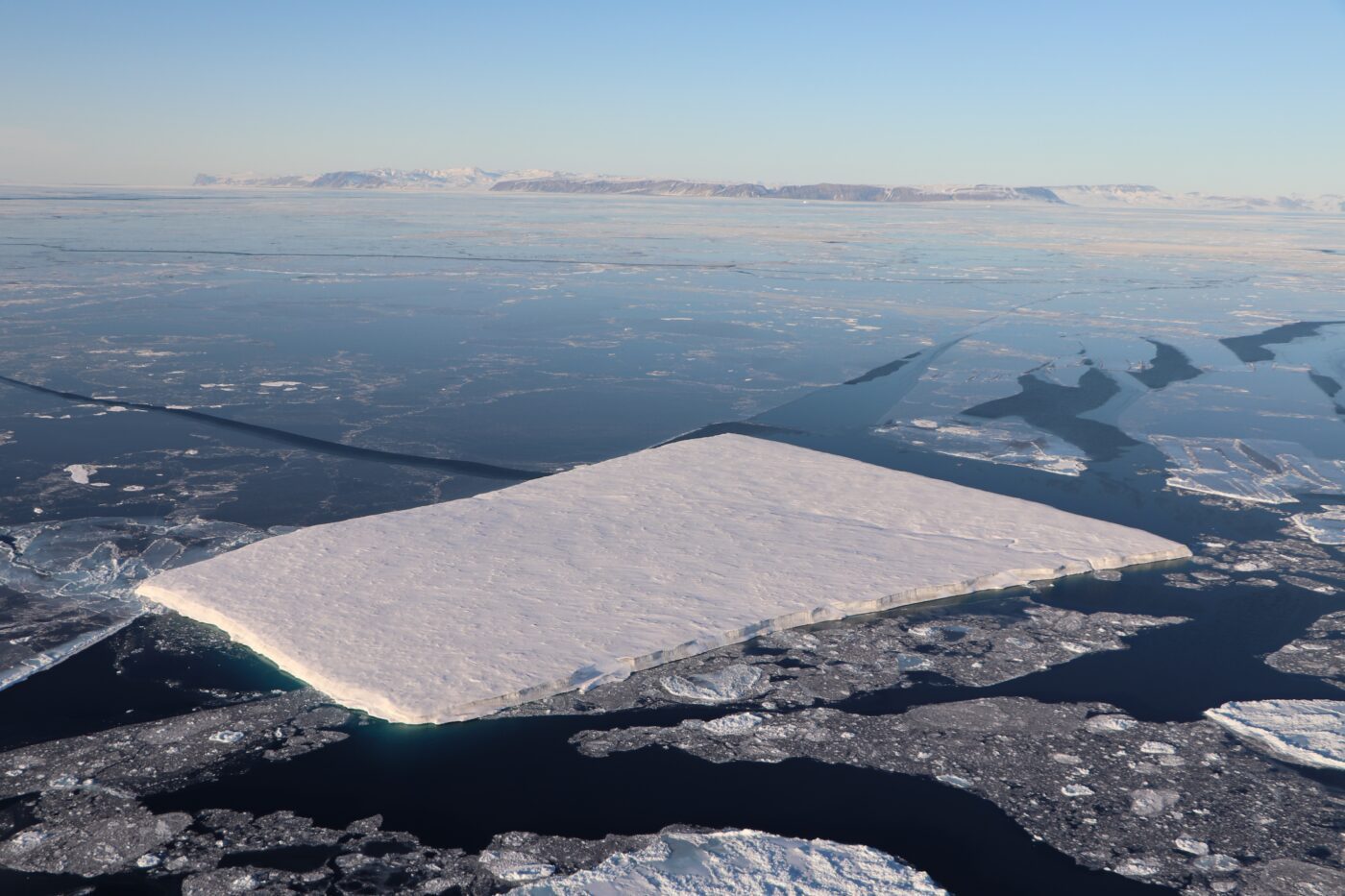

One of my most memorable moments was flying by helicopter to land on icebergs in the Arctic Ocean and deploy my Cryologger tracking beacons. Among them was an ice island, a large tabular iceberg that broke away from the Milne Ice Shelf on the northwestern coast of Ellesmere Island in 2020. Measuring about 2.5 kilometres long and 2 kilometres wide, it had drifted hundreds of kilometres along the coast. Standing on such a massive moving piece of ice was a surreal experience.

I founded the Cryologger project with the goal of making polar research more accessible, and the 2025 Amundsen Expedition brought the total number of Cryologgers deployed since 2018 to 40. Seeing my instruments transmit data in real time from such a remote and harsh environment reminds me of how far the project has come and the new opportunities it creates for Arctic science.

From your perspective, what are the main challenges or key learnings you experience in your work field?

Because my work depends on helicopter operations, one of the main challenges is the unpredictability of Arctic weather. Conditions such as fog, high winds, or poor visibility often determine what is possible and can quickly alter research plans. This is an inherent part of Arctic fieldwork and has taught me the importance of flexibility and preparedness. It has also underscored the value of patience and teamwork, since so much depends on coordination between pilots, crew, and researchers. When conditions are right, it opens the door to science that is both exciting and highly fulfilling.

Adam’s work on glaciers and icebergs not only deepens our understanding of climate change, but also inspires a more attentive and respectful perspective on the Arctic and its challenges. Through his projects, we gain a clearer sense of the impact icebergs have on our planet.

Photos credits

Alexandre Livernoche, Environment Climate Change Canada

Alexandre Normandeau, Natural Resources Canada

Erika Brummell, University of Ottawa

Adam Garbo, University of Ottawa